Chapter Two

(there’s a reason why it’s chapter two and not chapter one – trust me on this 🙂 )

It’s not a good idea to wake up in a mortuary. It’s likely that there will be an awful lot of screaming.

In my experience, it’s not necessarily the mortuary staff who do the yelling; they’re probably used to the occasional stiff suddenly sitting up and demanding a cup of tea. No, it’s the pseudo-corpse itself. One thing you can guarantee once you’ve safely been declared dead is that any pain killers they might have given you earlier will have run their course and any stitching will be purely cosmetic.

In my case, the screaming was also caused by claustrophobia. Being shut in a tray in a fridge in a body bag doesn’t rank on my list of favourite experiences to repeat any time soon.

But there I was, not dead, with a body that couldn’t tell me which bit was hurting the most, yelling my head off and adding insult to injury by bruising my arms as I tried to break out of the bag.

Some months later, when I got some much-needed counselling, I overheard the therapist talking to her superior.

‘She has irrational fears of being trapped in a drawer, of being attacked by a shark and of being abandoned.’

‘Has she ever been trapped in a drawer, attacked by a shark or been abandoned?’

‘Yes. All three.’

‘Then they’re not irrational fears, are they?’

I got a referral.

On the day itself—and thankfully it was daytime—there were staff in the mortuary who heard my yelling and banging and opened the drawer. And it could have been worse: I would have hated to have woken up during a post mortem. Or at any time that they were replacing my blood with formaldehyde.

Underneath the pain and the confusion, there was also an indescribably weird feeling of machinery attempting to start up when it’s old and rusty. My blood had spent some time obeying gravity but, now, it had to pull itself together and work out how best to start flowing again.

My heart was pounding pistons on a steam engine and my whole body felt like a puffing and blowing, ageing walrus heaving itself out of a hole in the ice.

Then it really got confusing. I was on a trolley, being wheeled up and down corridors, with people sticking needles and drips in me and asking if I knew my name and who was the prime minister. The first bit was easy: ‘Bella Ransom,’ though they didn’t seem impressed. The second bit, I was inordinately proud of: ‘Tony Blair.’

That went down like a lead balloon.

‘She thinks the prime minister is Tony Blair … she thinks her name’s ‘handsome.’ Did she have a CAT scan when she came in?’

‘No, she’d been pronounced dead.’

‘Ah. Better get one now then… definitely something going on in the brain.’

You think?

What was going on in the brain was a mélange of thoughts, memories, screaming and regret.

You see, after the first, scary part, the whole being dead thing had been really rather nice. Obviously, we don’t get told that or we’d all start jumping off bridges or allowing ourselves to be eaten by sharks. But it is.

When the panicking people gave me an anaesthetic so they could start sorting out whatever it was that had killed me, I thought for a joyful moment that I might be going back.

No such luck.

Next time I woke up, I was Bella Ransom, aged six, lying in a children’s ward. My dad was sitting in one of those high-backed chairs, asleep. I had no idea why I was in hospital but a quick check proved that I still had both arms and legs so it couldn’t be too bad.

‘Daddy,’ I said quietly. He opened his eyes and smiled at me.

‘Possum,’ he said lovingly; the nickname that only he ever used.

‘Is Mummy here?’

He shook his head, and took my hand.

‘Darling Possom,’ he said. ‘We’re having some trouble re-establishing reality. We’ll get it sorted soon, I promise. Try not to worry.’

‘Okay.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about but it didn’t matter. I was so sleepy.

For a while—maybe days?—I kept moving in and out of sleep and different realities. At one point, I was 21-year-old Bella Ransom, just graduated from Uni, travelling in Australia with my friends, Josie and Ben. Tony Blair was prime minister and I lived in Bristol. I’d been attacked by a shark. Another quick check established that all limbs were present and almost correct though my right thigh which had taken the brunt of the attack was heavily bandaged and hurt like hell.

Another time, I was Bel Nazam, aged 29, in yet another hospital. It was night and the humming and bleeping sounds were different. A kind nurse told me that the timeline was still out of kilter and offered me a cup of tea. I said, ‘yes please’ and promptly fell asleep again.

Then, it was Jon who was sitting in that high-backed chair that skulks by every hospital, bed. He was dozing.

‘Hey,’ I said, quietly, feeling relief flood through me. I knew that I was 17. I must have mistaken Jon for Dad and it had all been a dream, what with the dying and all. I wondered why I was in hospital now but I was obviously more or less in one piece so I could relax.

Jon opened his eyes, smiled and took my hand. He raised it to his lips and then leant forward.

‘Bel,’ he said. ‘It’s going to be a bit rocky for a bit longer but hold on. It’s nearly sorted.’

I just smiled and nodded and drifted off again.

I woke up again, alone in another hospital, still tied up with tubes, I could still remember being dead and I still thought the prime minister was Tony Blair. They told me I was Bel Nazam and I knew that Jon and my parents were dead; so long ago that grief was only a soft sorrow. but I couldn’t remember where I lived, who, if anyone, I was with or even what I did for a living.

‘It will all come back,’ said the registrar brusquely. She seemed to know what she was talking about but that was no comfort right now.

There wasn’t a lot of comfort anywhere. This time, I was in Eilat in Israel. I’d been attacked by a shark (what, again? Or was it the first time? Truly, I didn’t know) while snorkelling in the Red Sea but it wasn’t a shark bite that had killed me because this had been a rather unimpressively small shark—it was smashing my head on a rock while trying to avoid it that did the damage. Apparently, I had drowned which is why I was still alive. Bodies do strange self-preservative things when they drown. Even so, to be attacked by a shark once is unfortunate; to be attacked by one twice looks like carelessness…

It appeared that I was on holiday on my own. Nobody had come to enquire after me. This did not encourage me to believe that this particular incarnation of Bella Ransom-Whatever was living a particularly fulfilling life. Luckily, others in the water had dragged me out before said shark could get another bite at its lunch. Sometimes, people doubted the existence of all these sharks in later years but all I ever had to do then was show them the bite-shaped scar on my leg. Or was that the Australian one?

Shit.

Okay, what do I know? I was compos-mentis enough to look around me and discover that I had a beach bag containing a wallet, a towel and some very stale food that I had obviously nicked from breakfast in a hotel. Not a lot of money, a driver’s licence with my unfamiliar name on it, but no mobile phone and no clue as to where I was staying.

No hospital that is used to regular inundations of stupid tourists who have fallen off unsuitable horses, drunk themselves silly or had the temerity to interfere with any local wildlife with teeth, is going to be one of the kinds of locations where you’re going to get any extra level of nurturing. I think they’d have discharged me when I came round from surgery if I’d been able to walk. But I was interested in the fact that I knew that. A young Bella wouldn’t have done.

It was all rather overwhelming, not to mention confusing so I went back to sleep.

When I woke up, I was still in Eilat. Progress then.

The ward sister was staring at me crossly, tapping beautiful white teeth with a Parker pen.

‘You can get up and go,’ she said in accented English. ‘There’s nothing wrong with your head but a bump and your leg is barely scratched. We have other patients who need your bed.’

‘But … but I… you just operated…’

‘We were going to operate,’ she corrected me. ‘We thought there was pressure on the brain. But the CAT scan showed there was nothing wrong. You can go.’

I sat up. And I could sit up. No tubes attached.

‘But I was dead.’

‘You’re not dead.’

‘Don’t you want to keep me in for observation. I was dead!’

‘No,’ she said. She was being very emphatic. ‘You weren’t dead. You were unconscious.’

No, I bloody wasn’t. Whatever the hell was going on, the dead bit was the only constant I had.

‘I’ve lost my memory,’ I said. ‘I don’t know who I am or where I’m staying. I don’t know where to go.’

‘You’re staying at the Almog Hotel,’ she said. ‘You can get a taxi.’

‘The what hotel?’

‘Almog. A … L … M … O … G.’

But how do you know that?’

‘Pshaw,’ she said, or something similar and stalked away.

I felt a lump in my throat but I bloody well wasn’t going to cry. Whether I was nine, 19, 29 or (horrifyingly) much older, I’d always been stubborn about that. I’d cry on my own but not in public. No one but those I loved got to see me cry.

‘Get a grip,’ I said to myself, wrapping my arms around my body to hug myself.

I rocked back and forward for a minute and then took a deep, deep breath.

Okay, Bella, get practical. Take a good look at your body. What kind of shape is it in, in this particular moment’s reality?

Relatively good. I gave a sigh of relief. I could feel that there was a part of my head that was shaven with a large plaster attached but I appeared to have hair and, from what I could see, it was about shoulder length and dark. Tentatively, I raised the sheet and saw two, fully present legs. One thigh had a huge, ugly, old, jagged white scar that looked very much as if it might have been a shark bite and two straight scars where the repair scaffolding had gone in and was strapped up just below the knee.

Hadn’t I just been bitten? Again? I guess that was the wound, if so. A gentle poke elicited the answer. Ow.

I pondered who might be prime minister and realised it must be David Cameron. So, I was about 35 then. I could handle that. Though why I might be in Eilat was quite beyond me.

Carefully I went through my bag again. The picture on my driving licence looked like a 40-year-old woman.

Oh crap.

I was sore and confused, but mobile and the sooner I got out of here, the better. There was a swimming costume, sundress, sunhat, towel and sandals in the bag and I probably did have enough cash to take a taxi to the hotel. Then, I could find my room and discover who the hell I really was; what I was doing here and when I was due to go home … not to mention where that might be, who might be there or whatever it was that I did for a living. I thought I was an archaeologist specialising in ancient languages. I knew I had been an archaeologist and I liked being an archaeologist and I couldn’t see why I’d have changed that. Perhaps I was on a dig out here? That would make sense. But why hadn’t someone enquired for me? How…? What…?

I got out of bed, shakily, and managed to walk to the bathroom. I gulped when I saw myself in the big mirror there. This was definitely a much older Bel than I expected which meant that more than a dozen years of my life were missing. Even worse, I’d got a lot fatter. A wave of loss and deep loneliness came over me. It wasn’t as though I hadn’t travelled alone in my youth—I’d done a lot of travelling. But right now, someone to love me and hold me and tell me it would all be okay would really, really have helped. I couldn’t even remember who the hell had given me the surname of Nazam which was as perplexing as it was annoying. Certainly, he wasn’t around right now. That is, if he even was a ‘he.’ I simply didn’t know.

I walked out of the bathroom and directly into Jon. He caught my upper arms and looked deep into my eyes.

‘We’ve stabilised the timeline,’ he said. ‘We had to divert you here to sort out your injuries; we shouldn’t have, technically, but we’re going to need you in the land of the living. Get some rest and I’ll be back when I can.’

And he was gone.

I sat down heavily on the hospital bed. I’d gone mad. There was no other explanation. While I tried to sort my head out, I looked through my wallet.

Hidden behind some debit cards, I found a folded-up Post It Note:

You are Bella Ransom.

You are currently 43 years old and single.

You live at the Old Rectory, Tayford, Devon.

You work in between worlds in soul retrieval.

You are protected.

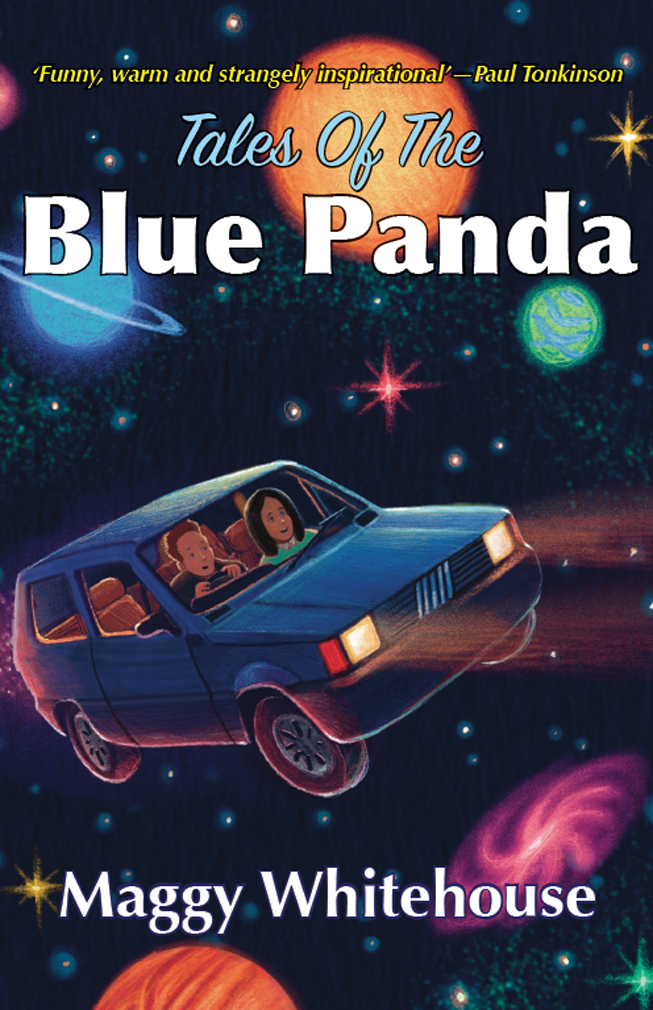

Jon will come to fetch you in the blue Fiat.

You went night riding with Josie in Rador when you were 16. The pony was dun with two white socks. There were five stones, not four.

Bel x

No one but Josie and I ever knew about the night riding or the hidden fifth standing stone in the meadow.

I am Bella Ransom and it would appear that I retrieve souls.

0 Comments