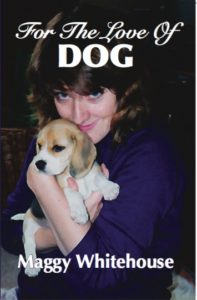

Read Chapter One of Maggy’s new novel For the Love of Dog for free. If you like it, you can purchase your copy here.

Read Chapter One of Maggy’s new novel For the Love of Dog for free. If you like it, you can purchase your copy here.

I am 39 years old and I am out of nice.

I have done nice all of my life. I have been an angel. I have looked on the bright side. I have compromised and helped. I have done pathetic. I have done the tears.

But I ran out of nice about six weeks ago. It’s gone, vanished, simply disappeared. I don’t know where it went and, of course, as I don’t have it any more, I don’t give a toss about losing it. It’s quite comforting really. Not in a nice way, obviously. It’s simply different.

There is not a cell in my body which has not felt the pendulum swing.

That is why I am currently holding up a queue of perfectly pleasant people at Heathrow airport and refusing to get on an aeroplane. Yes, they are going to miss their take-off slot; yes, they are all going to be inconvenienced and yes, quite a few people are getting seriously irritated. But they cannot go without me without even a further delay because my luggage is on board.

What is not on board is my dog. And I am not going without her.

I am a strange phenomenon in this world of possessions. I have no keys, no car, no job, no money and no home. All I have is two suitcases, a holdall, a laptop computer and a beagle. Logically, these are all fairly important to me—not least the beagle.

And Heathrow appears to have lost her.

Even if I were not already out of nice, I would be running dangerously low by now.

The idea is that my dog and I are transiting through London on our way from Denver, Colorado to Malaga, Spain, to live for seven months in a tiny village in the mountains south of Granada. We lived in Colorado for five years, in the days before my husband Alex decided that I had outlived my usefulness and left me. The problem is that Alex is the one with the visa. And to remain in the USA without a visa (or, for that matter, the income that goes with it) is not a good idea. So, I have to leave.

Of course, it is far more complicated than that. It always is. But to go home to England is not an option for me right now for it would mean months of hell in confinement for a very spoilt little bitch. And the dog wouldn’t like it, either.

Anyway, I’m not sure if England is my home any more; I left it, willingly enough, five years ago and never expected to return except for holidays. In fact, I’m not sure of anything. I’m going to live in a house I’ve never seen in a village I don’t know, in a country whose language I don’t speak and where I don’t have any friends. Except Frankly.

So, I am not boarding this aeroplane without her. I am being perfectly pleasant about it—pleasant is different from nice. You can be pleasant and obstinate; pleasant and firm; pleasant and downright bolshie; pleasant and adamant. I am all of those.

‘Well I suggest that you find her,’ I say calmly when the airline clerk says that they have lost my dog.

And I smile sweetly. It is not a nice smile.

‘I can wait,’ I say. ‘I have all the time in the world.’ And I have. I have the rest of my life and nothing whatsoever to do with it. So, standing at an airport departure gate being obstinate is as good a way of passing the odd hour or two as any other.

Frantic telephone calls are being made. To do the airport staff justice, they don’t want to lose a dog either. It would be pleasant for all of us if they could discover where Frankly is and get her safely on that plane.

If I could have flown her directly to Spain from Colorado, I would have. It’s bad enough for an animal to have to fly, in a box, alone in darkness with all those strange feelings that they can’t understand without having to do it twice over in one day.

But there was really no alternative and, when I arrived at Heathrow and went to the Information desk to check that she was okay, they told me that she was being loved and petted and fed and fussed over by a whole load of people in the kennels.

‘She’s probably being far better looked after than you,’ they said.

Yes, probably—but it is my first time in England for three years and, even if it is only an airport, it is good to see the old familiar shops and hear the (lack of) accent.

It is also so peaceful to be able to buy a meal without having to have a relationship. In the States I could not open my mouth without the response: ‘You’re not from round here, are you?’ or ‘Gee, I like your accent.’

Even so, I loved Colorado. Beautiful, beautiful Colorado.

Alex, Frankly and I were happy there even after such a huge transition. Frankly was the best friend you could ever want when starting a new life. She pottered through everything in her own comfortable manner, moving from chasing squirrels to chipmunks and from rabbits to raccoons with no effort whatsoever, and she was always there and comfortable and furry whenever I felt worried or upset. And she made friends for me too. So many American people every day stopped and petted this sweet and sassy tricolour beagle, falling in love with her kohl-ringed brown eyes and soft white muzzle with the dash of white running up between her eyes. ‘So cute!’ they said. ‘So cute!’ And from there, conversations could start and friendships be forged.

I once asked a friend if Frankly were spoilt. She thought carefully for a long time and said: ‘No, she’s not spoilt, Anna. She’s ruined!’

The trouble is that beagles are as addictive as cigarettes, alcohol, chocolate and drugs. You think you can handle it; that you can quit any time you like; but the truth is that you are hooked. Fortunately, beagles don’t like cigarettes, alcohol or drugs but from then on it’s a fight to the death for the chocolate.

I know I should add here that chocolate is bad for dogs — can even be fatal — and shouldn’t be fed to them. But I only learnt that long after a lifetime of beagles all of which had, at some stage, stolen vast amounts of chocolate without any bad effects. Lily scoffed a two pound box given to me for my 18th birthday and littered the lawn with silver-paper-coloured dump for days. Never turned a whisker.

It’s traditional to blame your mother for any addiction and my mum certainly initiated our family beagline addiction when I was very young. It was after Dad had left; Richard my brother was eight and I was six so it was entirely understandable. Aromatherapy was not readily available in those days and hugging was not then fashionable, let alone accepted in Mum’s family circle. Beagles, on the other hand, were very paws-on and definitely smelly. But, despite the infinite furry rewards, the eager wet noses and the soulful eyes, it was a long and exhausting life of beagledom. In fact, Mum told me once that she thought that raising children had been a piece of cake in comparison. Richard and I had come when we were called; rarely stolen from the larder, never chewed her shoes or clothes, slept in our own beds and went off to obedience school five days a week for fourteen years.

I did not even have an adolescent rebellion; I was too awash with beagle puppies to fall in love with pop stars or ponies. But when Richard and I both went away to University, some kind of Cosmic Law took a hand. The last beagle went to the happy hunting ground and Mum was left alone in the house. It was not an easy time for her but, with the help of friends, a little alcohol and quite a lot of chocolate, she made it through. She was over it. She was in recovery. She got a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.

It is said that whatever you do, you will eventually end up like your mother. I did not believe it myself but ten years after the last childhood beagle went chasing celestial rabbits, Danny died in that stupid accident and I decided to get myself a puppy. I was working part-time as a pastry chef and the rest of the time from home as a cookery writer and part-time in the evenings as a pastry chef so it was feasible.

‘Mum,’ I said, casually over Sunday lunch at her place. ‘If I got a dog, would you be willing to look after it one or two days a week while I’m at work?’

‘What sort of dog,’ said my mother suspiciously.

‘Oh, a beagle,’ I said airily.

There was silence. I looked at Mum and she looked at me. A long struggle was going on inside her. Finally, she spoke.

‘Three days a week,’ she bargained ruthlessly.

Frankly arrived six weeks later. She had a worried little puppy brow that wrinkled when she tried to think and she did a lot of thinking; almost as much as she did sleeping (and that was mostly on a cushion next to my computer keyboard).

She followed at my heels, snuggled into my arms, whimpered when I left her and made it totally and abundantly clear that she was mine for life as long as I obeyed her every whim. We compromised on that after a battle of wills that brought on my first grey hairs. I won a few points and Frankly learnt to sit, stay, beg and shake hands. She never, ever walked to heel.

But she was there in the evenings when Danny’s pictures spoke of the love and laughter that we had shared. She was named after him in a way—Danny had had a habit of saying ‘Frankly, this’ or ‘Frankly, that’ and we had made up an invisible friend and a private joke that ‘Frankly’ always had an opinion on anything.

The furry Frankly was only downstairs in the kitchen and could be fetched and held tightly in the nights when Danny’s ghost was not there to comfort me and the tears would not stop. She was someone to care for when there was no Danny to kiss me or tell me that he would be perfectly safe and it was just another, normal, diving trip.

She was there too, when the anger finally surfaced; the anger at Danny’s carelessness and bravado and belief that he was immortal. His disregard for my fears as he went diving ever deeper and longer in the cold, hostile waters of the North Sea. She was there when my memory haunted me with the bitter hours when they searched for his body; when people tried to be hopeful and I knew full well that Danny’s oxygen would have expired. It took three days to find him and they would not let me see his body.

One day, I threw Danny’s clothes and equipment into black plastic bags and took them to Oxfam but, when I got back, Frankly was curled up in the now empty wardrobe. Danny’s clothes and fading scent had been part of Frankly’s life, too, and she did not understand why they had gone. We sat in the wardrobe together and I cried and Frankly licked me and then we decided to eat a pot of ice cream together. It was Frankly’s idea.

Slowly, life rebuilds itself. When someone you love dies, part of you dies too. But there is a resurrection. I recovered. I met Alex and I loved him.

And now, here I am, waiting at Heathrow and an adapted quotation from Oscar Wilde is running through my head “To lose one husband is unfortunate. To lose both looks like carelessness.” But Alex has gone and he, too, is not coming back.

There will be time enough in Spain to go over and over what has happened. Just be aware that I am not going to be nice about it. I am not going to be understanding; I am not going to see Alex’s point of view. I tried all that and it didn’t work.

‘Anna, are you running away?’ asked my mother when I told her of my plan.

Yes I am. It is easier to be honest when you don’t have to bother being nice.

‘Oh look!’ The nice (really nice) female flight attendant is looking out through the window. ‘Is that your dog?’

I jump up and together, the three airline staff and I peer down at the tarmac. A wooden ‘sky-kennel’ is being transported towards the plane on a hand-pulled trolley. The end with the wire grill is pointed towards us and a little brown and white face is peering out anxiously.

‘Oh! How cute!’ say the airline staff and my heart melts too. It is Frankly and she can do cuter than cute without even trying. As we watch, two stewardesses on the tarmac run up to the kennel and start trying to stroke her through the wire. How could anyone resist such a sweet little dog, especially one that pathetic?

The relief is so great that I can feel a slight edge of niceness warming my fingertips. I even smile at the officials as I take my boarding pass and walk down to the plane.

It doesn’t last: I am so tired and there is so much more to do. I can feel the strength seeping out of me as the aeroplane begins the slow taxi to take-off. Deep in the bowels of the plane, Frankly is probably wondering what is happening to her and why it is happening again, and I am looking in a tired and confused way at the last of England not knowing what I feel.

Take off is achieved. I unfasten my seatbelt and sit back in the narrow seat. A drink would be wonderful: a gin and tonic or even a whisky. But I daren’t have a drink because I will have to drive more than 150 miles once we have arrived in Malaga. Numbly I ask for a tomato juice and eat as much as I can of the in-flight snack because I will need to keep my strength up.

There is a stewardess on the flight who reminds me of Ella. She has the same height and dark striking looks and the same proud way of walking. In the past she would have intimidated me but seeing her now brings a rush of warmth to my heart.

Ella the Californian has been my best friend these last three years. It was Ella who taught me how to be strong and where the borderline is between being reasonable and a doormat. It was Ella who took me to task over packing up Alex’s things.

‘Anna, the bastard has left you!’ she said. ‘He has walked out leaving just a letter behind him. He has left you alone in a foreign country without a visa or money. He has dumped you like a worn out old mattress and you are packing up his Dresden china!’

‘It was his grandmother’s,’ I say rather sheepishly. ‘It’s not her fault.’

‘She’s dead, right?’ says Ella.

‘Yes, she’s dead. But his mother’s still alive and it’s not her fault either.’

‘There I disagree,’ says Ella, picking up the box which I have just finished packing and sealed with tape. ‘She raised him. And it’s not like he hasn’t done this before, right?’

While I ponder this, Ella has walked to the front door of our lovely colonial house with the wooden porch and white railings. She stands at the top of the steps and looks back at me.

‘Anna, watch and learn,’ she says.

The box arcs upwards as it leaves her arms and everything goes into slow motion. I am on my feet with my mouth open and my hands out as if to try and catch it.

The sound of the smashing china is astonishing. It is so final; so destructive; so utterly vengeful. I am awed.

‘Your turn,’ says Ella, once the last tinkle and crunch has died away in the gentle wind that ruffles the broad-bladed grass by the sidewalk.

‘My turn?’

I could not have done what Ella has done. But the worm did begin to turn. Niceness has no place in my life now. ‘Quite right,’ says Ella. ‘Be wonderful, be kind, be loving, be horrible, be outrageous, be unreasonable. Just never be nice. Nice is just nothing.”

‘Can I get you anything else?’ says the stewardess who looks so much like Ella.

‘No thank you,’ I say, smiling. ‘You have already done more than you could possibly know.’

It is dark when we arrive in Spain which, for some reason, surprises me. I think I’m expecting it to be tomorrow morning. But the air is very different and foreign, filled with the buzz of activity and strange scents. What will Frankly think of it? Or of the different language spoken by the people who will be unloading her from the plane?

But there is no time to worry about that; the worry is reserved for getting a beagle, hand-luggage and two suitcases through Spanish customs simultaneously when I hardly speak the language. But I have a phrase book and I have learnt a few simple syllables so I can just about manage ‘¿Donde es mi perro, por favor?’ to the fierce looking woman at the information desk.

The trouble with speaking a foreign language is that people reply to you in that self-same language and then you are buggered. Because, for all the sense it made to me, her reply could have been ‘Where you left it.’ There is an impasse where a tired and confused British woman looks hopelessly at bored and irritated Spaniard but the woman at Information relents. She is pointing towards the baggage carousel where the suitcases are—and, sure enough, there is the sky kennel jolting through the rubber flap along with a pile of other cases.

Frankly is on her feet inside, squeaking loudly. You get superhuman strength when you need it and I dive across the hall and lift the whole contraption off without even thinking. At once, I am surrounded by customs officials demanding the documentation which is strapped by tape to the kennel with duplicates (and triplicates) inside my holdall, just in case.

Six pages of information in English and (bad) Spanish and they want to look at everything.

Frankly is still whining so I call to her lovingly, trying to be reassuring. My two suitcases lumber past behind my back but they don’t matter. Knowing that Frankly’s paperwork is clear is far more important.

Oh God! How much longer are they going to take? They are obviously searching the documents for one in particular. Is it there? The authorities in Colorado scarcely knew how what was needed to get a dog to Spain and the Spanish Embassy in California was curt to the point of hostility when asked for help and advice.

I rustle through my bag to see what else there might be. Here is the health certificate, stamped and ratified by everyone I could think of, the export certificate (ditto) in triplicate with its Spanish translation. Here are the various vaccination certificates—what else could they want?

Nervously, I proffer the last little letter hand-written by the vet and painstakingly translated by Ella’s friend, Carmen the Mexican, from the taco house on Main Street. It certifies that Frankly is a household pet and not being imported for show or breeding.

The officials share it around between them, nod wisely and beam at me. That is what they wanted! They all put the documents on top of Frankly’s wooden box and stamp them vigorously, making the little beagle jump.

I feel the relief flood through me like a river of heat.

I make gestures asking if I can open the cage but no, not until I have shown the papers to more officials at the exit, so I am dragging the kennel across the floor with Frankly crying inside, showing the papers to yet more officials and then, worst of all things, having to leave her outside, in the box, while I run back to grab the cases.

I had a trolley—but it has gone, so both cases must be pulled simultaneously across the floor and through customs back to where Frankly is. And now there is a crowd of kids around the sky kennel banging on the roof. They think it’s funny.

Before I have even thought, I have boxed the ears of two of them and shouted at the rest. They scatter like ninepins and I almost fall at the door, snatching at the locks and letting my little beagle out. She jumps into my arms and wails with delight.

‘Oh Frankly!’ I gasp and let the tears come because we are here and we are safe together and nothing else matters.

Until the next bit.

The next bit is getting all the cases and the dog (not forgetting the holdall and the laptop which have been on my shoulders all the time) down to the car hire area. The only way to do it is to abandon the sky kennel for the moment. Luckily, this is Spain and nobody comes trailing after me shouting about it and, even luckier, all my car hire documentation is in order too. Within 20 minutes all the cases are in the Fiat Punto, Frankly has found something similar to a dandelion in the open-air car park which is of sufficient quality to merit the depositing of a huge puddle of pee—and I can breathe again.

There isn’t any room for the sky kennel anyway so I’m not going back.

Okay.

That was easy enough. All I have to do now is drive for two and a half hours in the dark in a strange car, on roads I don’t know with only meagre instructions to guide me. And I’m heartbroken, jetlagged and exhausted from a 16-hour journey. Should be a piece of cake.

For five minutes I sit with my face buried in Frankly’s fur, stroking her back and stomach and listening to the beagle’s snuffling, huffily noises as she paws at my face and licks me. Then I take another deep breath, start the engine and drive out into the Spanish night.

Malaga is busy tonight. The bright lights strobe across the wide, vehicle-filled roads and cars weave back and forwards in a dance they know intimately. I am a good driver and I cope—as I always do—but it helps to swear and curse as I swing the wheel to dodge another overtaking car that cuts in front of us too close. I squint at the signposts that are approaching too fast for comfort, looking for the road to Motril. Ben’s voice echoes in my ears with the directions. Whatever I do, I must be in the right hand lane or I will end up in Cordoba.

When people back in England heard that Alex had left me they said things like ‘Well you’re so strong, you’ll cope.’

Thanks a bunch, I thought at the time, hearing ‘Oh Good, I don’t have to do anything to help you’ in the background. But what could they have done to help anyway? I was in Colorado and, by then, Alex was back in England. Friends in Colorado were different—but Americans are another species.

Rather homesickly, I think back to my friends: beautiful Ella and circular Gilbert the failed restaurateur. In days when I thought I would never laugh again they had me in hysterics and not always because they intended to. Ella, particularly. Now that’s a strong woman if you like.

What do people mean by strong anyway? Does it mean that you don’t just lie down and die? But who does? Does it mean that you just don’t act like the half-destroyed mess that you are? Did the people who say I’m strong think that because I was able to talk to them on the telephone without crying that I didn’t weep and howl and hate and want to die? That I didn’t care that much?

Who knows? I’m too tired to think. I have a long drive ahead and a beagle who is frantic for company and reassurance, trying to climb onto my lap. Poor love, how can I expect her to understand anything?

‘No, Frankly! Not now.’ Not now that I am trying to negotiate a Spanish dual carriageway in the dark. Around me the drivers from hell are holding a competition to see who can shave the most paint off the hire car’s bodywork without actually leaving a dent.

Frankly puts her ears down and looks pathetic but I can’t afford even to put out a hand to stroke her. The traffic is vile and, despite everything, I still want to live.

There must have been an angel somewhere because suddenly we are on the right road and out of the city. It’s virtually motorway and I can relax a little. My hand goes out to the soft, furry head and Frankly sighs as I massage her ears. By rights she should be in the back but there’s no room for both the suitcases in the boot.

‘We are going to a lovely village,’ I tell her. ‘A place where we can stay for seven months. Then we can go back together to England. Frankly, we’re going to be safe.’

Frankly whiffles at me. Where’s My Supper? she is saying and I realise that I, too, am starving.

Twenty minutes later, we are sitting outside a little café in some unknown Spanish town which has been carved in two by the main road. I am eagerly eating fried chicken and rice and sharing it with Frankly who has forgotten everything except the lure of food. This place smells different and that was all very interesting until the waiter arrived with chicken. Now it is of no importance whatsoever. Food is food and it is Frankly’s god.

I have ordered a bottle of wine and another of water and the one glass of alcohol that I am allowing myself is rough, red, warming and comforting. The temptation to have more must be very firmly resisted though and I re-cork the bottle with a presentiment that it may be needed later when we get to Los Poops.

But for now, this is lovely. The café is too close to the road for real comfort but the four little tables on the pavement are gaily covered in red and white check tablecloths, helping me to feel festive. The waiter doesn’t care who I am or how I might feel and serves me with the panache of a sulky sixteen-year-old but the food is good and fresh and every mouthful brings back strength.

As I sit back, replete and happy with still half a glass of wine to savour, it is safe to think back to Ella and Gilbert without too much homesickness. I am in the middle of an adventure now and adventures are fun. Ella would enjoy this.

It is a good road to Motril, thank God, and the traffic is dying down by the minute—but that has its drawbacks because now I have time to think. It is too dark to enjoy the scenery and there is no radio in the little car to distract me. Alex’s voice starts talking in my head, justifying, telling me that it is all for the best and that he didn’t leave me for Suzie. Suzie was only 10 per cent of the reason; 90 per cent was the bad state of the marriage, he is saying—just as he said in the letter.

Yes, I remember, the marriage that was so bad that he made love to me and told me he loved me on the last morning that we were together, before he met her; before he ran away from everything we had ever built together as if it had never existed.

And I am lost in that hideous downward spiral of self-justification and pain which is so real that it feels as if there is nothing else. My whole body is heavy with anger and grief and I am not concentrating on the road.

The car weaves slightly across the central line and an oncoming lorry blares its horn, making me jump and sending a rush of prickling sensations of fear down my arms and back. My attention is snapped back to the present. Before I know it I am in a tunnel and, because it is night and there are no lamps on this road, there is no light at the end of it. It could go on forever. Oh great. Wonderful symbolism. Thanks a bunch! ‘Cut it out!’ I shout at any passing deity that might be listening.

Then the car shoots out into unexpected moonlight, then back into another tunnel. There is a dance of darkness and shadows for mile upon mile but then the mountains recede and the tunnels are over and we dive into the night itself—a world of deep velvety blue and grey. To my right, the sea is dark and calm and wide, dominated by a great silver three-quarter moon. Its light glitters across the water, drawing a magical luminous pathway, and a beloved memory slips into my mind dispelling the echoes of both Alex and of fear.

It is of a book I read as a child, The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald. Irene, the little princess, could always escape danger by looking for the lamp burning in her grandmother’s room high in the turret of the castle. It was a magical lamp which could be seen through rock or wood and it always guided her safely back home.

When Danny died, I saw that lamp in a circular globe of light through a neighbour’s window as I sat in my darkened bedroom staring blindly down the garden with no hope and no future. It lifted me then as it does now.

Grandmother’s lamp. We must be nearly home.

Ben warned me about the turn-off to the village so it is fairly simple to spot it in good time and I only miss it twice and have to do dangerous U-turns which wake Frankly from a deep and peaceful sleep on the front seat beside me. She sits up, scenting the end of the journey and sways from side to side, looking at me resentfully as I negotiate the final ten kilometres of potholed concrete track up into the mountains around what seems to be a hundred hairpin bends. Turn after turn, I swing the wheel backwards and forwards as the headlights arc out over echoing nothingness. I can feel myself dredging up a few prayers from nowhere.

At last, I can see the village lights ahead. ‘Thank you, God,’ I say in relief—then swear violently as another hairpin takes me by surprise.

The road swings off to the left into yet more mountains but Los Poops is to the right and I can coast gently into the small village square surrounded by tall whitewashed houses with big, closed, dark wooden doors glowering at any stranger who might pass.

We are here. I stop the car and lean forwards to rest my head on the wheel in exhaustion and relief. Ben’s soft voice giving me directions to the little holiday home that he has lent me indefinitely echoes in my sleepy brain. ‘As soon as you turn into the village, there is a doorway with two steps to your right. Park just beyond it because the street to the house is too steep for a car.

‘It is called Calle La Era. The house is two thirds of the way down, next to the village shop; there is a little courtyard to the left and the door is there, on the right.

‘The light switch is to the left of the door. Don’t worry if the lights don’t go on; the fuse may have tripped. There are candles in the kitchen drawer and the fuse box is next to the cooker. Enjoy, Anna. Mi casa es su casa.’

Oh joy. Bed is just another 20 yards away. Frankly shakes herself, eager to get out and explore. There are lights on the sides of the houses so I can see my way.

‘Come on, Frankly.’ I open the car door and she follows me out, flopping down onto the cobbles, her nose twitching at all the strange and humid smells.

There is a lamp showing the name ‘Calle la Era’ plainly but the street itself is virtually perpendicular. With laptop and holdall swung on my shoulder I make my way downhill, my legs almost buckling in exhaustion. Frankly follows cautiously. This Road’s Wrong, she says. What Have You Done To It?

‘Nothing, honey,’ I say. ‘It’s what happens on mountains.’

I have a habit of answering Frankly’s alleged thoughts. Now we will be living alone together that will probably get worse. Still, it’s better than talking to yourself.

This must be the courtyard. This must be the door. A great dark wooden slab in the white wall with great metal bolts all over it. And the great, old key, sent so lovingly to me in Colorado by Federal Express, must fit into it somewhere.

It takes an age, for the lock is loose and old and it is an art form to open it. Amusement turns swiftly to irritation as I jab it, push it, bully it, coax it; but eventually it turns just before temper gets the upper hand—and the door is open.

Frankly stands nervously at my feet as I fumble for the switch. Are There Dragons? she asks with a nudge of her nose on my leg.

‘Probably,’ I say. ‘But not the sort that eat beagles.’

That’s All Right Then.

Click.

Nothing. The darkness doesn’t even flicker. Oh God. Now I have to find my way to the kitchen in the pitch black and find the fuse box. Stumbling, I feel my way along rough walls. My sight is clearing and I can see both the cooker and what looks like the fuse box. Yes, one of the switches is down. I flick it and light floods through the house.

In a haze of relief and exhaustion I slide down the wall to the floor and sit looking around me while Frankly has a good sniff around.

No Dragons So Far, she reports, nose quivering with interest.

‘Oh good. I’m glad to hear that.’

It is so pretty. One complicated open-plan little room comprising kitchen and living room with whitewashed walls, French windows and a red tiled floor. Old wooden beams loom above in the roof and there’s a huge arched skylight above them. The far wall is completely covered with books so old and dusty that you can hardly read the names. It looks as if no one has been here for months, if not years. All the plants around the window are dead and plaster is flaking off the walls.

Never mind. A shower, a drink and bed are all I need (a bath would be better but I have been forewarned that there isn’t one). Ben has told me how to light the immersion heater which gives constant hot water so that’s the first important thing.

Seven attempts and a glass of wine later, the immersion heater lights. Only then do I discover that there isn’t any water and I sit down, suddenly, on the floor again and start to cry with great sobs of hopelessness. It is too much.

Frankly paws at me as I sit in the dust on the floor with hands on my head, sobbing and rocking myself like a child. The cold wet nose pushes into my face and she starts to lick the tears but that only makes me cry the more.

The cases in the car must wait. Everything must wait. I must get to bed and finish this day. I have had enough. In the tiny single bedroom by the front door, there is a double duvet packed in polythene. I pull it roughly out and throw it onto the mattress.

Lock the front door. Go to the kitchen and drink down another glass of wine in the hope that it will make me sleep and pour a little of my precious bottled water into a bowl for Frankly. She drinks it thirstily. Now, get into bed in your clothes because, guess what—oh perfect!—the duvet is damp and unaired. I am totally miserable, lonely and lost but within minutes, a warm little creature has clambered up beside me and curled up against my stomach.

Frankly doesn’t mind the squalor, my dirty body, the tearstained cheeks or the damp bedding; we are together and that is all that matters. She sighs contentedly and falls asleep.

In books you would sleep well, but this isn’t a book, it’s real life, and I sleep appallingly, even with my own personal bed-airer and hot water bottle snoring rhythmically beside me. Thoughts circle in my mind until I think I’m going mad but, when dawn approaches and the first glimmers of light creep across the floor, things begin to feel better. Together, Frankly and I have aired the duvet with our bodies; the first light is wonderfully encouraging and, when I get up to go to the loo and pull the chain with an automatic reflex, it flushes.

Hallelujah!

Yes, the taps are working—and there is a pile of towels in the bathroom cupboard. I am in the shower as fast as can be and the instant-heat immersion works! Oh this is so pleasant! There is even a scabby bit of soap.

So I wash Colorado out of my body, fill several saucepans with water in case this wonderful flow is purely temporary and brew a cup of black tea with a very old teabag from a jar by the cooker. Then I sit by the French windows, wrapped in towels and eating the last of my chocolate and watching the colours of the sea far below as the great, golden sun slides over the horizon. The waves, so distant, are like silver, the crinkled moon, just setting, sends ripples of light across the water and, above in the brightening sky, there’s a wispy pattern of cirrus clouds, luminous with yellow and gold. I have to shade my eyes to watch this clear, dawning beauty as it spreads across the waters to Morocco and it is one of those moments that imprints itself in memory as a treasure for all time.

I’m going to be okay. I really, really am.

For the Love of Dog ©Maggy Whitehouse 2016. Purchase your copy here.

0 Comments