Mary Magdalene has always been one of the most misunderstood – and unfairly reviled – women in religious history. She is still misinterpreted by those who wish her only well and who see her as the Holy Grail, the wife of Christ. Her relationship with Jesus has had to be downgraded into marriage in order that people can attempt to understand it. Obviously, if they had as special a relationship as the Gnostic Gospels of Philip and of Mary Magdalene suggest, they must have been lovers. Not at all. That is classic first-half-of-life binary thinking.

Let’s start with the famous Da Vinci Code claim that Leonardo Da Vinci painted Mary Magdalene sitting next to Jesus at the last supper. In the book, by Dan Brown, the hero, Robert Langdon, looks at the painting and has the stunning revelation that the image of St John is, in fact a woman. Yes, it certainly looks like a girl. And if this were the only painting where the apostle John looked a little effeminate, then he might have a point. Unfortunately, it is not.

Leonardo was not even a ground-breaker in painting an effeminate male in a painting about Jesus. He lived between the years of 1452 to 1519 but earlier, in the fourteenth century before he was even a dot of paint in his father’s eye, Paul, Herman and Jean Limbourg, from Nijmegen in what is now known as the Netherlands, were painting Les Très Riches Heures – a magnificent Book of Hours for the Duke of Berry. One of the images from that work represents the healing of the possessed boy in Mark 9:17. The boy is full grown but a very androgenous figure with tumbling long dark curly hair and a feminine face and elegant hands. The only way you could tell he was male was his muscular legs.

Even more telling is the image of the Apostle John in the Flemish artist Juste the Gand’s Last Supper, painted in 1474. John is beardless and wearing a feminine-style cape of entirely different style from that of all the other disciples. You could easily believe he was a girl.

Some people say that Leonardo Da Vinci was gay. Certainly, in 1476 he and three others were anonymously accused of having sex with a beautiful boy model and male prostitute called Jacopo Saltarelli. The accusations were dropped without trial but, given that there is no trace of a woman in Leonardo’s life and that there is evidence of a series of beautiful boy apprentices of apparently little artistic talent, homosexuality is an understandable assumption for a more tolerant modern world to make. However, in those times the devotion to classical Greek art and the beautiful young men depicted in ancient statues was extremely fashionable and Leonardo was not the only painter to be surrounded by young male muses.

One more effeminate John is to be found in Ford Maddox Brown’s 1848 Pre-Raphaelite painting of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. John is blond and girly – and one of the other disciples has his arm around him in a protective hug.

So, lovely story though it is – and important as Mary Magdalene may have been – the idea that Leonardo is painting a woman holds very little water. What is so interesting is how many people want and need this modern legend to be true. There certainly is evidence that there might have been something special between Jesus and Mary, especially in the Nag Hammadi scrolls. These scrolls notably include the Gospels of Thomas and Philip and (unofficially) include the Gospel of Mary Magdalene herself which was discovered in Cairo.

So let’s look at all the evidence we have about Mary Magdalene.

She is mentioned in all four Gospels and each one acknowledges that she was the first witness of the risen Christ (Mark is a bit doubtful here because scholars believe that the ending of the Gospel of Mark was tacked on a few years after the original was written). Mary Magdalene is named twelve times in the Gospels but only one is placed before the crucifixion (Luke 8:02). There is one at the cross (John 19:25) and there are ten after Jesus’ death, including two mentions of Jesus having driven seven devils out of her (Mark 16:9 and Luke 8:1). Only three of the mentions also include another woman called Mary; probably Mary of Bethany but this is unproven. Those texts that write solely of Mary Magdalene are Mark 16:9 and John 20:1 and 20:18.

Apart from the fact that Mary Magdalene is the person charged with telling the disciples the news that Jesus has resurrected from the dead, I would say the most telling story about her comes in Luke:

“After this, Jesus traveled about from one town and village to another, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom of God. The Twelve were with him and also some women who had been cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary (called Magdalene) from whom seven demons had come out; Joanna the wife of Cuza, the manager of Herod’s household; Susanna; and many others. These women were helping to support them out of their own means.”(Luke 8:1-3)

This is a distinct statement that Jesus’ ministry was supported by wealthy women, one of whom was Mary Magdalene. Had she been his wife, her money would have belonged to him and this mention is unlikely to have been made. It is important to emphasise that the earliest available evidence shows women did have their part in Jesus’ ministry as his followers.

One of the earliest of all original texts that is known today is the Dura-Europus scroll which dates back to the second century CE. This translation by D.C. Parker, D.G.K. Taylor and M.S. Goodacre (Studies in the Early Text of the Gospels and Acts, p. 201): “of [Zebed]ee and Salome a[nd] the women [amongst] those who followed him from [Galil]ee to see the cr[ucified one].” The sections in [ ] are missing but Salome and women “those who followed him” is clearly stated.

Probably the most common misunderstanding about Mary is the idea that she was the woman with the alabaster jar who anoints Jesus when he is at the house of Simon the Pharisee. The Gospels have four stories of the anointing of Jesus by a woman but none identify her with Mary Magdalene. In the earliest versions (Mark 14:3-9 and Matthew 26: 6-13) the unnamed woman is not identified as a sinner and she anoints Jesus’ head (in those days this could be seen as an indication of Jesus’ coming death). John (11:2) identifies the woman as Mary of Bethany and has her wiping Jesus’ feet with her hair after anointing him.

Luke (7:36-50) tells the story much earlier in Jesus’ life, saying that the unidentified woman is a repentant sinner who weeps, wipes Jesus’ feet with her hair and anoints them with perfumed oil. He tells her that her faith has saved her which is slightly different from driving seven devils out of her. The idea of driving devils from someone was associated either with madness or severe sickness and this woman obviously had neither. Her actual sin is not identified; nowhere is there any indication – other than the sensual smell of spikenard oil, that it is sexual in origin. All that libel came later.

The Gospel of Mary dates back to about 125 CE which makes it one of the oldest texts of the early Christian Church apart from the four Gospels themselves. It is part of what is known as the Berlin Codices and was not discovered with the 13 texts found at Nag Hammadi. It is often thought to be one of these because it is of similar date and origin and is referred to by scholars as being a part of the Nag Hammadi Library. In it, Mary Magdalene is clearly shown as having special understanding of Jesus in the often-quoted extract from chapter five: “Peter said to Mary, ‘Sister, we know that the Saviour loved you more than the rest of women.’” But the rest of that chapter, which takes place after the resurrection, makes it clear that this is a spiritual relationship, not a physical one. It reads:

“….they were grieved. They wept greatly, saying, How shall we go to the Gentiles and preach the gospel of the Kingdom of the Son of Man? If they did not spare Him, how will they spare us?”

Then Mary stood up, greeted them all, and said to her brethren, ‘Do not weep and do not grieve nor be irresolute, for His grace will be entirely with you and will protect you. But rather, let us praise His greatness, for He has prepared us and made us into Men.’ When Mary said this, she turned their hearts to the Good, and they began to discuss the words of the Saviour.

Peter said to Mary, ‘Sister we know that the Saviour loved you more than the rest of woman. Tell us the words of the Saviour which you remember which you know, but we do not, nor have we heard them.’

Mary answered and said, ‘What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you.’ And she began to speak to them these words: ‘I, she said, I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to Him, Lord I saw you today in a vision.’ He answered and said to me, ‘Blessed are you that you did not waver at the sight of Me. For where the mind is there is the treasure.’

I said to Him, ‘Lord, how does he who sees the vision see it, through the soul or through the spirit?’

The Saviour answered and said, ‘He does not see through the soul nor through the spirit, but the mind that is between the two that is what sees the vision and it is ….’”

The rest of this chapter is missing.

Wife or prostitute?

The two phrases that cause all the excitement, particularly in Holy Blood, Holy Grail and The Da Vinci Code, come from the Gospel of Philip, which was found at Nag Hammadi. The first one is: “There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary, his mother, and her sister, and Magdalene, the one who was called his companion.”

The better-known quotation is:

“And the companion of the […] Mary Magdalene. […] loved her more than all the disciples, and used to kiss her often on her […] The rest of the disciples […]. They said to him ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?’ The Saviour answered and said to them, ‘Why do I not love you like her?’”

Many researchers and books have added in the word “mouth” for where Jesus placed his kisses. This is pure supposition. That part of the text is lost in a torn corner.

And why, if Mary Magdalene is Jesus’ wife, is anyone surprised that he should love her more, or kiss her? Surely they would be surprised if he did not. No one ever asks my husband why he loves me or kisses me!

In Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, Sir Leigh Teabing specifies the word “companion” to be the Aramaic “wife”. As mentioned previously, the Gospel of Philip is written in Coptic, probably translated from Greek, and not in Aramaic and the author uses two different words for companion, one Greek – koinonos – and one Coptic – hotre. Neither is known to be used anywhere else in ancient texts to mean wife.

Koinonos appears in the New Testament seven times (Matthew 23:30, Luke 5:10, 1 Corinthians 10:18, 2 Corinthians 1:7, Hebrews 10.33, Philemon 1:17 and 2 Peter 1:4). Never once is it used except for man-to-man or human-to-Christ relationships. The word wife is a challenge in the New Testament because the word gunay is used both for woman and for wife. But in the King James Version it is used to mean wife 71 times in the New Testament and the only exception (1 Peter 3:7), is the use of the word gunakeios which means “belonging to the woman/wife/feminine”. The word koinonosmeans fellowship or sharing with someone or in something ranging from friendship to business.

In the Journal of Religion and Popular Culture (Vol XII), Dr Nancy Calvert-Koyzis of King’s University College, University of Western Ontario, makes it clear that in the Gospel of Philip, when someone is spoken of as someone’s wife, the Coptic word for wife is used rather than the Greek or Coptic for ‘companion’ (Gospel of Philip 70, 19; 76, 7; 82, 1). What is also apparent from the Nag Hammadi Library Gospels is that the disciple Peter did not like Mary or her influence. This is the Peter who became the foundation of the Roman Catholic Church.

From the Gospel of Mary: “Peter asked the others about the Saviour. Did he really speak with a woman in private? Should we all listen to her? Did he really prefer her to us?” And: “Levi said to Peter, you are always angry. Now I see you are arguing against this woman like an adversary. If the Saviour made her worthy, who are you to reject her?”

From the Pistis Sophia (the most extensive Gnostic scripture known before the discovery of the Nag Hammadi scrolls, believed to have been written in the third century and preserved in what is known as the Codex Askewianus): “Mary came forward and said ‘My Master, I understand that I can come forward at any time but I am afraid of Peter because he threatens me.’”

John Dominic Crossan, Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at DePaul University, Chicago, and author of 20 books on the historical Jesus including Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, Who Killed Jesus and The Birth of Christianity(HarperCollins) sums it up for me beautifully when he says: “They didn’t attack Mary Magdalene because she was Mrs. Jesus. They attacked her because she was a major leader, that she was up there with Peter and the rest and they fought like hell to put her back down in her place.”

So how did this woman, portrayed in so many Gospels, turn into a repentant prostitute? It didn’t start out like that, according to early Church literature. The second century church father Hippolytus describes Mary and the other women disciples as Brides of Christ, faithful women who redeemed the disobedience of Eve. In his commentary on Solomon’s “Song of Songs” in the third century, St Hippolytus even gives Mary Magdalene the title of “apostle to the apostles” and her star remained bright up until the fifth century when Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, also described Mary Magdalene as the New Eve clinging to Christ as a Tree of Life and redeeming the unfaithfulness of the first Eve. Other Church Fathers, Tertullian, Origen, Dionysius, Pseudo-Clement, Ambrose, Augustine and Gregory of Antioch were also strong in her praise.

It was only at the end of the sixth century that Mary Magdalene the prostitute hit the headlines. Pope Gregory I decided that it was too confusing to have so many different women in the Gospels, especially several called Mary, and ruled that several of the un-named mentions of women must be of Mary Magdalene. In an Easter sermon in 591 he is reported to have said, “She whom Luke calls the sinful woman, whom John calls Mary, we believe to be the Mary from whom seven devils were ejected according to Mark. And what did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices?”

The vices he was referring to were the seven cardinal (or deadly) sins as defined by – guess who? – Pope Gregory I himself. They are extravagance (later translated as lust), gluttony, greed, sloth (laziness), anger, envy and pride (also translated as vanity).

Pope Gregory’s ruling was at best careless and at worst ignorant as the Gospel of John states clearly that the woman with the alabaster jar was Mary of Bethany not Mary Magdalene. Both appellations denoted the town of origin of the woman concerned and acted in the way that surnames do today.

Even so, Gregory did attempt to rehabilitate Mary in the same speech: “She turned the mass of her crimes to virtues, in order to serve God entirely in penance” (the seven holy virtues being chastity, temperance, charity, diligence, meekness, kindness and humility) but, even so, a legend was born.

However, the Eastern Christian Church tradition did not support Gregory’s view and continued to teach that all the women disciples were representatives of the New Eve, the church and that Mary Magdalene joined with Mary, Jesus’ mother, and John in Ephesus, to become martyrs.

Ironically, Pope Gregory’s misinterpretation, which grew as only a good story can, made Mary Magdalene far more interesting especially to artists who, by the time of the Renaissance, were having a fine old time with half-naked women at the foot of the cross.

Legend after legend grew up around her. In one, she went into the desert to live as a hermit; French medieval tradition believed that Mary Magdalene was Mary of Bethany and that with her brother and sister, Lazarus and Martha, sailed to Aix, in what is now France. Lazarus became the first Bishop of Marseilles, Martha defeated a dragon that was threatening the region, and Mary converted the king and queen of Southern Gaul to the new faith. The cult of Mary Magdalene spread across France, and relics of her body are alleged to be kept at many churches. This medieval legend assumed that she was a former prostitute, but had been redeemed through Christ.

This is the legend made popular by Margaret Starbird’s novel The Woman with the Alabaster Jar (Bear & Co.) which writes of Mary’s and Jesus’s daughter, Sarah, becoming the founder of the Merovingian dynasty of French kings.

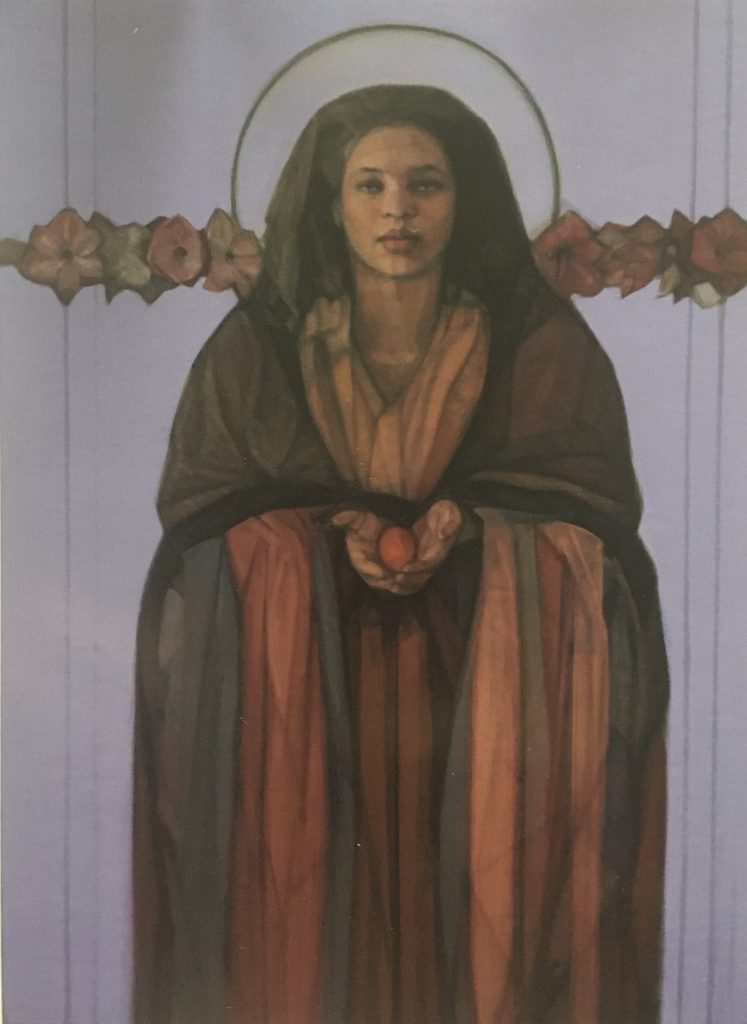

Mary’s story inspires us today because she fills the vacant space of the Divine Feminine in the Protestant religion. We think that if she were so close to Jesus that she was the first to witness the resurrection, she must have been his lover or wife. But it is far more likely that she was his soul mate and that his destiny was inextricably entwined with hers. She was ‘the apostle to the apostles,’ the one who truly understood the meaning of kenosis or the outpouring of steadfast love. Let us honour her as that and seek to be more like her; not requiring of recognition but simply doing the Work to our full ability and allowing the Christ consciousness to be our guiding force.

0 Comments